The impacts of sanctions and counterterrorism measures: Data collection toolkit

3. Global sanctions and counterterrorism framework

What are sanctions and counterterrorism measures?

Sanctions and Counter-Terrorism Measures (SCTM) are strategic tools leveraged by States, regional bodies, and international organisations (UN) and designed with the intention to counteract and neutralise threats to peace, security, stability, human rights violations, breaches of international humanitarian law, and impediments to humanitarian aid delivery.

Additional sanction regimes are employed in situations of non-proliferation and armed conflicts. Their objectives range from gaining political leverage to facilitating political resolutions, or to curtailing specific technological capabilities of certain groups. Over the past half-century, SCTM have evolved from comprehensive sanctions to more targeted ones. Since the 2000’s, all new regimes (or “smart sanctions”) have been designed to have a limited, strategic focus on specific individuals, groups, or undertakings. Most frequently implemented measures include travel bans, asset freezes and arms embargoes.

These measures either necessitate proof of intent or knowledge that the funds will contribute to a terrorist act, or require evidence that the funds will be utilised to the advantage of terrorist organisations or individual terrorists. Although SCTM are a key instrument to many States in promoting international peace and security, research and humanitarian organisation practices indicates that these measures can, whether inadvertently or not, impede principled humanitarian action. They create hurdles for the delivery of humanitarian assistance in regions where terrorist groups are active, despite states' obligations under IHL to facilitate humanitarian access. The ICRC estimates that 60 to 80 million people live today under State-like governance by armed groups.

The humanitarian community maintains a neutral stance on the legitimacy of SCTM. However, the impact of these measures on principled humanitarian action is now widely recognised and our objective is to mitigate their unintended negative effects.

Sanction regimes: coercive tactics deployed by international bodies, governments, or groups of states to exert economic, political, or diplomatic pressure at different levels. They encompass a range of actions, including economic sanctions

like asset freezes and arms embargoes, diplomatic sanctions like severing relations, and individual sanctions such as travel bans and asset freezes imposed on entities designated as "terrorists". It’s worth noting that these sanctions can originate

from counter-terrorism efforts, exemplified by instances like UNSC Resolution 1267.

Counter-Terrorism (CT) measures: they encompass actions and policies implemented by governments, international and regional organisations, and institutional donors in their collective effort to fight terrorism, including its funding. These measures manifest in various forms, such as legal frameworks (international sanctions, criminal codes, specific legislations, etc.) as well as overarching policies.

The history of counterterrorism measures

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, a progressive enforcement of counter-terrorism and anti-money laundering measures has taken place at global, U.S., and European levels. U.S. Executive Order 13224 notably directed attention towards curbing financial support for "Specially Designated Global Terrorists" (SDGTs) by imposing asset freezes on foreign entities linked to terrorism in an unprecedented manner. This order introduced the concept of extraterritoriality, extending its reach to encompass any individuals or entities connected - directly or indirectly - to U.S. persons and organisations.

On the international front, the adoption of Resolution 1373 (2001) by the United Nations mandated member states to adopt an array of measures designed to counteract and prevent new acts of terrorism, despite the absence of a universally recognised definition for terrorism.

Concurrently, alongside multilateral regulations, approximately twenty treaties addressing various aspects of terrorism constitute the international legal framework. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), initially formed in 1989 to combat money

laundering, expanded its mandate to combating terrorism financing. In 2001, FATF published nine recommendations, including Recommendation 8, which seeks to prevent non-profit organisations from being exploited for terrorism financing.

Several regional bodies have translated or taken unilateral sanctions. For instance, following the Paris attacks, EU Directive 2015/849 of 20 May 2015 was enacted to prevent the utilisation of the financial system for money laundering or terrorism

financing (AML/TF). This directive consolidated and harmonised financial system surveillance provisions, establishing a comprehensive legal framework in compliance with FAT recommendations. The "4th Directive" necessitates EU Member States to identify and mitigate risks associated with money laundering and terrorism financing. Subsequent Directives, such as the "5th" and "6th", expanded these provisions, enhancing transparency obligations in financial transaction and introducing new criminal measures, albeit without targeting humanitarian organisations.

The cornerstone of EU's criminal justice measures against terrorism lies within Directive 2017/542 (2017), which incorporates obligations for EU Member States in alignment with the Council of Europe, FATF and the UN. Importantly, it includes a safeguarding clause to protect humanitarian aid from criminalisation.

Accordingly, donors began around 2015 to include counter-terrorism clauses in funding contracts, requiring organisations to assess potential interactions between their staff, partners, and entities or individuals designated as terrorists. Other donors introduced a "duty of care" similar to due diligence to ensure their funding does not finance "terrorism".

The legislative arsenal against terrorism, accompanied by the looming threat of sanctions and legal actions (especially from the U.S.) for noncompliance by various entities, has driven private actors to formulate mitigation strategies. Banks, for instance, have adopted risk reduction strategies, known as “de-risking” by refusing to provide certain services, such as money transfers, to humanitarian organisations situated in regions affected by international sanctions or counterterrorism measures.

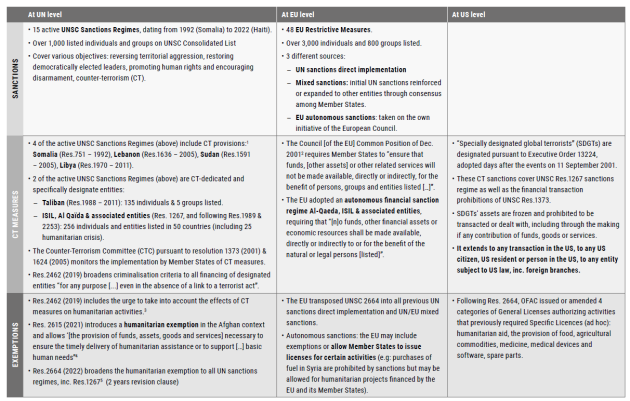

Examples of UN, EU & US sanctions and counterterrorism frameworks

Which laws applies to my programs?

The determination of the law applicable to a humanitarian program's situation can be based on several factors:

- The countries of registration of the implementing organisation.

- The country of intervention: humanitarian organisations have to comply with the laws of the country where their operations are carried out. These laws might encompass counterterrorism measures relevant to the country of operations.

- The nationalities of the organisation’s board trustees and collaborators in charge of implementing specific program(s).

The introduction of extraterritoriality in Executive Order 13224 (2001) by the United States significantly expands and complicates the

application of sanctions beyond national borders. This concept broadens the scope of sanctions to include any transaction, whether directly or indirectly related to a US citizen, US resident, US law-governed entity, or a US asset (including transactions involving US dollars). As a result, even transactions involving entities or individuals with no direct connection to the US, such as prior recipients of US grants, fall under the potential purview of these sanctions. This application can affect a humanitarian organisation located in a

country where it did not receive any US support, making it a complex and far-reaching measure with indirect implications.

Over the past decade, an increasing number of donors have incorporated counterterrorism (CT)-dedicated provisions into their funding agreements. These provisions aim to translate CT laws and regulations into concrete contractual obligations for funding recipients. Similar to de-risking strategies employed by the private sector or banks, these clauses are legally

binding, and failure to comply can have significant financial and reputational consequences, as exemplified in the court case between Norwegian People's Aid and USAID in 2018.

However, it's important to note that these provisions fall under civil law and, unlik state-enforced SCTM laws, do not typically lead to criminal prosecution unless explicitly stated otherwise.

SCTM Consequences

Typology of SCTM-related issues

Expand the sections below to find out more about the types of impacts that SCTM can have on humanitarian action and humaniatrian needs.

Screening measures are integral to NGOs' due diligence procedures. They aim to circumvent inadvertent engagements with sanctioned individuals. By utilising specialised software, NGOs assess potential suppliers, employees, and partners against diverse sanction lists. While this practice is prevalent among humanitarian NGOs, it is still extremely time-consuming.

However, extending screening to aid beneficiaries raises significant ethical concerns. Such an approach conflicts with the humanitarian principles of impartiality and independence, jeopardising the equitable distribution of aid based on needs. Denying access to vital assistance to any individual, even if designated, contravenes the fundamental ethos of such lists, and violates rights upheld by International Humanitarian Law. Notably, UN Security Council Resolution 2664 (2022) expressly authorises aid provision involving sanctioned entities. Implementing beneficiary screening could potentially impede the core mission of NGOs, compromise community trust, instigate data privacy issues, and potentially subject humanitarian organisations and staff to escalated risks.

Two main issues arise from ambiguous and nonprincipled requests or contractual clauses:

- They can expose humanitarian organisations to legal risks due to broad interpretations of terms like "terrorism" or "material support to designated entities" in sanction regimes and counterterrorism laws. Consequently, aid might be construed as supporting designated entities, potentially resulting in legal action against NGOs.

- They often enforce cumbersome compliance mechanisms, thereby escalating deciphering workloads and delaying aid delivery. Also, varied donor contractual clauses, inconsistent derogations and NGOs' limited understanding of these derogations could result in inadvertent non-compliance. This eventually obstructs localisation efforts due to the reduced capacity of local NGOs to effectively manage such obligations.

In addition to Member State scrutiny over support for designated actors, administrative limitations also arise from export restrictions to listed countries. For instance, purchasing dual-use materials in humanitarian contexts necessitates pre-emptive authorisations and comprehensive accountability reports, thereby escalating administrative workload.

SCTM-related challenges are not always explicit indirect impacts can emerge from the interpretation of these constraints by other actors such as banks. Over the past decade, states' stern warning to banks against financing terrorist-affiliated activities and entities has indirectly led to overcautious financial transfers to sensitive countries, many of which are humanitarian contexts (25 out of 50 countries liste on UNSC sanction regimes). This overcaution hampers INGOs from effectively channelling funds and may push some towards informal financial systems, ironically defeating the initial sanctions’ purpose. A similar phenomenon, referred to as de-risking, is prevalent among numerous international contractors and suppliers, who may inflate prices or decline contracts for countries seen as "risky" SCTM-wise.

Countries receiving humanitarian aid may also enforce their own counter-terrorism laws, aiming to undermine terror groups' operational capabilities and support networks. Unlike UN, EU or US sanctions, some of these measures are often indiscriminate and blanket-targeting. Examples include routine military screenings of specific communities, interdiction of certain modalities of intervention such as cash, lorry traffic restrictions or city-wide motorcycle bans.

These measures can affect humanitarian aid in several ways:

- Access constraints: They might involve limiting the movement of humanitarian agencies or populations, thus interfering with humanitarian activities.

- Criminalisation: The organisation or its staff may be viewed as colluding with a terrorist group, leading to potential criminal charges.

- Reputational damage: Public or political distrust can arise from perceived collusion with foreign governments or terror groups, damaging the organisation's reputation.

- Security incidents: These usually stem from reputational issues and involve decreased acceptance or even direct targeting by state or non-state armed groups.

- Impact on project planning and implementation as well as possible change of modalities of intervention or areas

These constraints and incidents often less monitored, largely due to the need for an in-depth understanding of the contextual legislation. However, they are just as likely, if not more, to hinder humanitarian aid compared to the international sanctions’ framework.

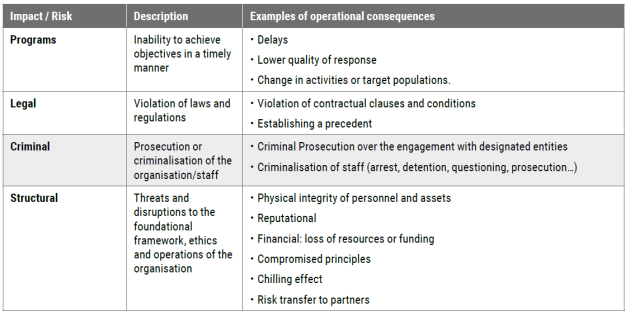

The ultimate ramifications of SCTM on humanitarian operators are complex and may involve overlapping effects that can be arduous to quantify. However, by employing a conventional risk analysis categorisation, the following types of impacts emerge that are the most likely to happen. The operational consequences above are not intended as exhaustive, and may be complemented by other types of risks identified by the organisation.

Direct or unintended harm to civilians

Due to its paramount importance for global peac and stability, Counter Terrorism initiatives often traverse the boundaries of International Humanitarian Law, manifesting through the following trends:

- Authorities/States deny the application of IHL to their counter-terrorism operations.

- Authorities/States label any act of violence by a Non-State Armed Group (NSAG) as an act of terrorism. This is despite the framework provided by IHL, which distinguishes between acts of terror and legitimate use of force in armed conflicts.

- Authorities consider that the exceptional threats posed by terrorism require exceptional response.

Those permissive interpretations pose a severe threat to the protection of civilians in armed conflicts and a risk of dismantlement of its standards.

Access to basic rights and aid

SCTM can have several impacts on populations, particularly in countries that are already vulnerable or unstable:

For feasibility reasons, and as detailed in the table on the next page, this data collection framework will primarily focus on the negative impacts of SCTM on the access of populations to humanitarian aid, complemented – when possible – by trends relating to human rights and access to health services.

The data collection tool was developed and designed by Action Against Hunger, Médecins du Monde, and Humanity & Inclusion.